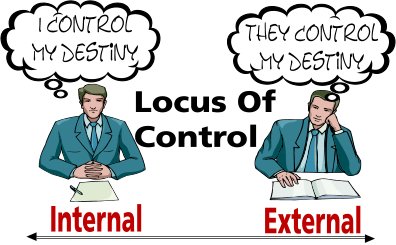

I have been reading about the idea of the locus of control. In brief, it is “the degree to which people believe that they, as opposed to external forces (beyond their influence), have control over the outcome of events in their lives“. I find that a challenging idea as it appears to not include any room for the Divine – that there is a Person outside of me that is in control of everything.

I think in his Journals Kierkegaard says that an all-powerful being is not all-powerful if that being cannot choose to not use all of their powers. And we Christians call that choice “love”. For me to love God, to choose Him, I must be free and God allows that freedom so that I can love Him. I know people theologically disagree – and I was raised in a tradition that does not agree with that idea of freedom. But I find that a comforting and challenging idea – I am free to love people and to love God without limit.

So back to the locus of control. Rather than not allowing for the Divine, it calls on me to “own” my choices. As I have worked with my counselor I have been encouraged to move beyond a “victim mentality”. And that movement has really helped me face my depression and my anxiety. These are not choices but how I react to them and how I live with them are my choices. In the past, I have made the wrong choices and those choices have hurt people.

So this morning I stumbled across this quote from Thomas Merton:

Today I seemed to be very much assured that solitude is in deed His will for me and that it is truly God Who is calling me into the desert. But this desert is not necessarily a geographical one. It is a solitude of heart in which created joys are consumed and reborn in God.

Sign of Jonas, 52

I think as Christians we can find our locus of control outside of ourselves. Christians have swallowed the scientific world view and elevated the “objective” to the role of the Divine. Simply to surrender to an idea, to a community, to a tradition, and to simply conform. Faith becomes an intellectual movement of non-questioning and just “doing”. Faith becomes an impersonal act. Of course, it is human nature to create that outside according to my experience and expectations. And, maybe even worse, it is human nature to expect that my “conforming” pleases God.

Maybe the Christian way of speaking about the locus of control is to speak about the “solitude of heart”? There is a place inside of me into which I can withdraw that I truly meet Jesus. And in this place, I surrender to Jesus. In this solitude, I listen to Jesus and have intimacy with Him. This place is not external to me but is the very nature of my being. My relationship is not only intellectual but personal and instinctive. Faith is personal and subjective. I experience Jesus in my “solitude of heart”.